Disqualified army hopefuls: ‘Shylocks have our IDs’

By Thokozani Mazibuko

For many youths in Eswatini, army recruitment is a lifeline out of poverty. Yet, for some, that hope is lost before it starts.

Eswatini Sunday, which has followed the recruitment process from day one, discovered that officials had disqualified some applicants simply because they did not have their National Identity documents. Local money lenders, commonly known as shylocks, held many of these documents.

At the dusty grounds of a recruitment venue in the Shiselweni region, disappointment was written across the faces of dozens of disqualified candidates. Among them was Sizwe Dlamini, who reluctantly admitted that he had been turned away because he did not possess his identification card.

“My passport is with my shylock,” Dlamini said quietly, his voice heavy with shame and regret. “I borrowed E600 to buy running shoes and food during training. When I couldn’t pay on time, he kept my passport as collateral.”

Dlamini is not alone. Out of every ten candidates who presented themselves at the army recruitment sites observed by the Eswatini Sunday, at least one was disqualified for lacking a valid ID document.

While some simply lost theirs or had pending replacements from government offices, a significant portion of these cases involved young men and women whose IDs were in the possession of informal money lenders.

What began as a personal financial struggle has now become a national issue. Youth unemployment in Eswatini remains stubbornly high, forcing many to depend on small loans from community lenders to survive or prepare for job opportunities like the army recruitment exercise.

However, these loans often come with harsh conditions. With little to no access to formal banking systems, desperate borrowers surrender their National IDs, passports, or birth certificates as collateral, a practice that is illegal under national laws but persists quietly in townships and rural areas.

One disqualified youth, who asked not to be named, explained how easy it is to fall into this trap:

“You can borrow E300 and be told to pay E500 in two weeks. If you fail, they take your ID or passport. You can’t even report them because you borrowed the money willingly.”

The interviewed army hopefuls disclosed that they were temporarily employed in the textile and security companies.

For others like Sihle Zulu and Themba Nxumalo, the disqualification was not only painful, it was humiliating.

“I trained for months,” Zulu said. “Every morning I ran 10 kilometres, hoping to join the army. But when they asked for my ID, I had nothing to show. I felt like crying because I knew I was capable.”

Nxumalo nodded beside him.

“This is a dream gone just like that. I know of more people in my area who are in the same situation,” he added.

The pair had travelled over 40 kilometres to the recruitment venue, borrowing money for transport and food, only to be sent home within minutes.

A social policy researcher who spoke to Eswatini Sunday under anonymity said the issue of shylocks holding IDs is a growing symptom of economic desperation.

“This shows how poverty and lack of access to formal credit systems push young people into vulnerable situations,” the researcher said. “An ID is not just a card, it’s a ticket to employment, education, and social services. Losing it means losing access to opportunity.”

He added that government and civil society must intervene urgently by providing financial literacy programs, affordable microloans, and strict enforcement against predatory lending practices.

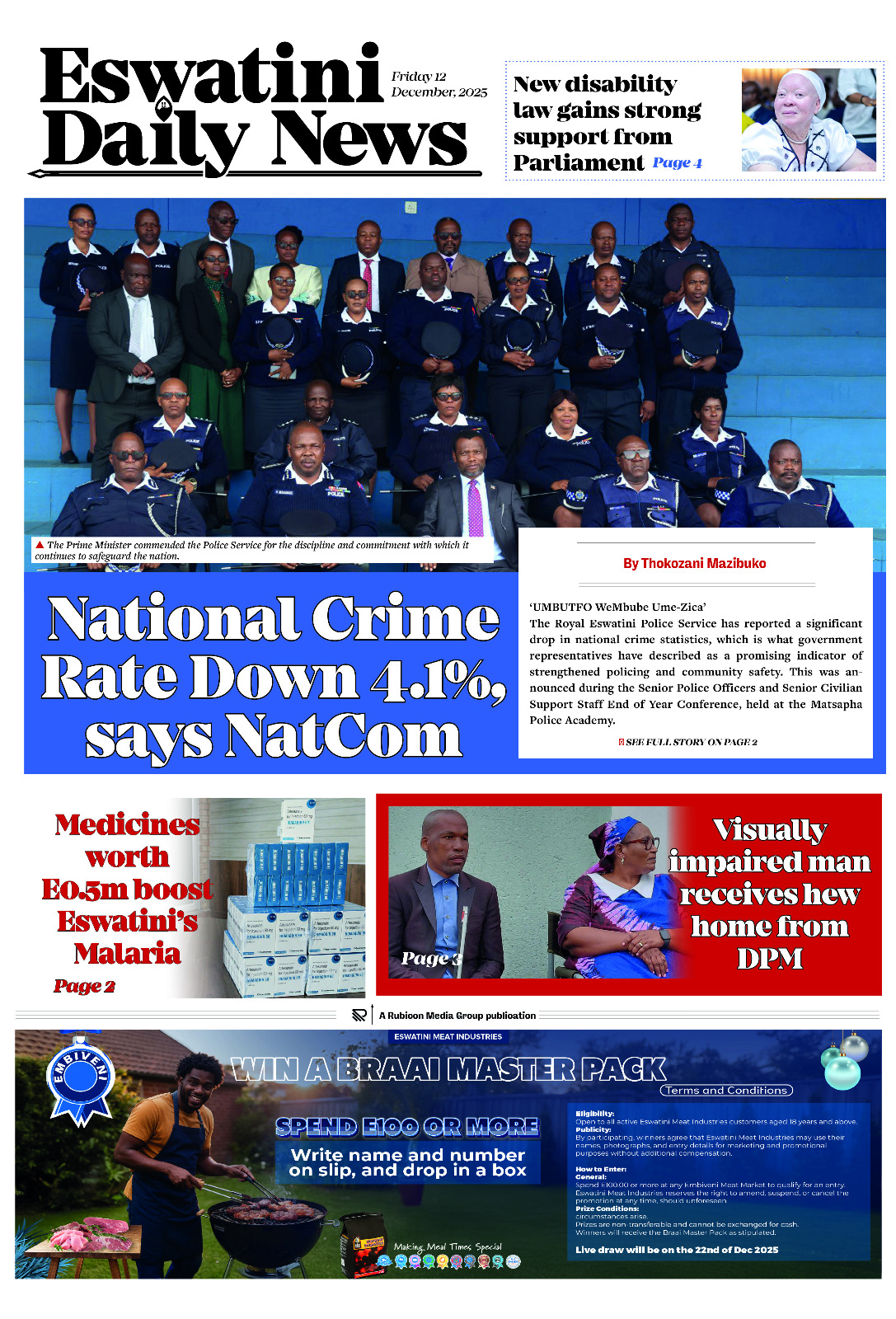

When approached for comment, Brigadier Sotja Dlamini, who is in the recruitment team, said that identification remains a non-negotiable requirement for all army applicants.

“We cannot consider anyone without a valid National ID or passport,” the officer said. “This is a matter of national security and verification. We sympathize with those affected, but the rules are clear.”

General Dlamini further urged young people to secure their documents and avoid situations that could jeopardize their eligibility for future opportunities.

In communities across Shiselweni and beyond, parents and elders have expressed concern over this growing issue. Some suggested that local leaders should collaborate with the Ministry of Home Affairs to assist youth who have lost or surrendered their IDs to shylocks.

A mother of one disqualified applicant told Eswatini Sunday, “These children are desperate for jobs. They borrow small amounts just to survive, but in the end, they miss out on bigger opportunities. The government must look into this.”

The ID crisis reveals a deeper truth about Eswatini’s struggling youth. They are willing to run, train, and serve, but they are being held back by poverty, debt, and lack of financial safeguards.

For Sizwe Dlamini and many others, the road to the army barracks may have ended this year, but their determination remains unbroken.

“Next year, I’ll come back,” Dlamini said with a faint smile. “But first, I have to get my ID back. Without it, I’m not a person.”

As Eswatini continues its national recruitment drive, Eswatini Sunday’s findings paint a poignant picture: a generation ready to serve, but trapped by the hands of informal debt. Unless urgent action is taken to address this shadow economy and its human cost, the cycle of poverty and exclusion may continue to rob the nation of some of its most determined and deserving citizens.

Accept passports and birth certificates – Army urged

A group of disqualified army hopefuls has appealed to the Umbutfo Eswatini Defense Force and the government to broaden the range of acceptable documents for nationality verification during recruitment.

The group, recently turned away for not possessing national identity cards, said they were unfairly excluded despite having other official documents proving their citizenship.

During interviews conducted by Eswatini Sunday, the young men and women, some of whom had trained for months in preparation for the recruitment race, pleaded with authorities to recognize passports and birth certificates as valid proof of nationality, especially for those facing challenges obtaining or replacing their ID cards.

“We are Swazis, born and raised here,” said one disqualified applicant. “Just because my ID is missing does not mean I am not a citizen. I have my passport and birth certificate; these should count too.”

Another applicant echoed the same sentiment, adding that technical delays and document loss have left many young people stranded during crucial recruitment periods.

“It takes months to replace an ID, and by the time it arrives, the opportunity is gone. The government should consider other official documents like passports, which are also issued by the same offices,” he said.

The group argued that the current system, which strictly requires a National ID card, inadvertently sidelines capable and patriotic citizens who have other credible forms of identification.

They urged both the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Home Affairs to review existing guidelines and adopt a more flexible approach in verifying citizenship during recruitment exercises.

“We understand the need for proper verification, but there should be room for fairness,” said one hopeful. “A passport or birth certificate is not fake, it’s issued by the same government that issues the ID. All we ask is to be considered on merit, not on paperwork.”

Many applicants lamented the challenges they face when trying to replace lost or damaged ID cards. Long queues, slow processing times, and shortages of materials at some registration offices have left numerous citizens waiting for months.

In rural areas such as Shiselweni, access to Home Affairs services can also be limited, forcing residents to travel long distances to regional offices, an expense many unemployed youth cannot afford.

“Some of us applied for replacement IDs long ago,” said a young woman from Matsanjeni. “The waiting time is unpredictable. Now we are punished for something that’s beyond our control.”

A governance analyst interviewed by Eswatini Sunday said that in many countries, passports, birth certificates, and voter registration cards are accepted as alternative documents when primary IDs are unavailable.

“This is a practical request,” the analyst explained. “As long as the document is legitimate and issued by the state, it can verify nationality. A rigid system risks excluding citizens who are already marginalized by poverty or bureaucracy.”

However, some officials have privately acknowledged the dilemma faced by youth in remote areas and hinted that future policy adjustments might be considered to accommodate exceptional cases.

For many of the disqualified applicants, the call for flexibility is not just a complaint, it is a plea for inclusion. They see national service as a path toward empowerment, stability, and dignity.

“We want to serve our country,” one hopeful concluded. “We are not asking for special treatment, just understanding. Let the government use all available means to verify us, not deny us because of one missing card.”

As the army recruitment drive continues across Eswatini, this appeal from the sidelined candidates raises an important question for policymakers: should nationality be defined by a single document, or by the collective evidence of one’s citizenship?