Traditional Knowledge: A Cornerstone of Eswatini’s Climate Strategy

By Nomonde Mafu

Ancient wisdom embedded in traditional ways of life may hold key solutions to today’s pressing climate crisis. This perspective has been underscored by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Climate, which recently emphasised that local communities globally manage 25% of the world’s land, safeguarding vital biodiversity and carbon sinks.

“Their traditional knowledge is crucial for effective climate policies and conservation efforts,” notes the UNDP communiqué.

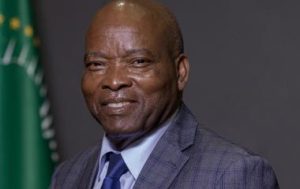

Eswatini is taking this message seriously. Renowned environmental scientist Dr. Wisdom Dlamini confirmed in an interview with the Eswatini Sunday that the country is actively integrating indigenous and traditional knowledge (ITK) into its climate agenda.

According to Frontiers, indigenous and traditional knowledge encompasses centuries-old wisdom, practices, and beliefs developed by communities through deep, generational relationships with their natural environment.

Passed down orally and through culturally embedded customs, this knowledge reflects an intimate understanding of local ecosystems, weather patterns, soil health, and biodiversity.

ITK guides sustainable resource management methods such as rotational farming, selective harvesting, and protection of sacred forests and rivers, areas that serve as biodiversity sanctuaries.

In Eswatini, these practices inform climate resilience strategies, from drought-resistant crop selection to timing planting using natural seasonal cues.

This worldview sees humans as part of nature, promoting reciprocal respect and stewardship, a vital ethos as modern climate challenges mount.

Since 2022, the Eswatini government has engaged communities to collect ITK as part of its National Adaptation Plan (NAP), building on commitments made in the 2021 Adaptation Communication to the UNFCCC.

Dr. Dlamini shared remarkable examples of how local natural indicators still guide communities. The calls of birds like umfuku and phezukomkhono signal the start of the wet ploughing season, while the playful behaviour of cows or croaking frogs foretells forthcoming rainfall. Even the way the moon rises can warn of heavy storms.

Traditional drought coping strategies such as kusisa (selling or relocating cattle) and choosing hardy goats are widely practised. Communities also harvest rainwater and diversify crops to boost resilience. Some engage in rituals involving water and salt believed to deter storms.

Furthermore, ITK underpins environmental conservation, strengthening community cohesion and stewardship. The Eswatini Environment Fund (EEF) champions projects using climate-smart agriculture and restoration of degraded lands.

It supports the protection of indigenous plants like incoboza lukhwane, used in handicrafts and preserving water quality, while also uplifting local incomes.

Traditional farming techniques foster ecosystem health and food security, with indigenous governance structures enabling adaptive responses to changing conditions.

Globally, indigenous-managed forests store more carbon, and practices such as controlled cultural burns reduce wildfire risk, highlighting indigenous communities as climate custodians.

Despite its value, ITK faces serious threats in Eswatini as modernisation, Western education, youth migration, and changing livelihoods erode traditional transmission, which is often oral.

Colonial legacies and misconceptions contribute to undervaluing indigenous systems.

Dr. Dlamini warns that preserving this living knowledge requires nationwide awareness campaigns, documentation, archival efforts, and research linking ITK with modern climate science.

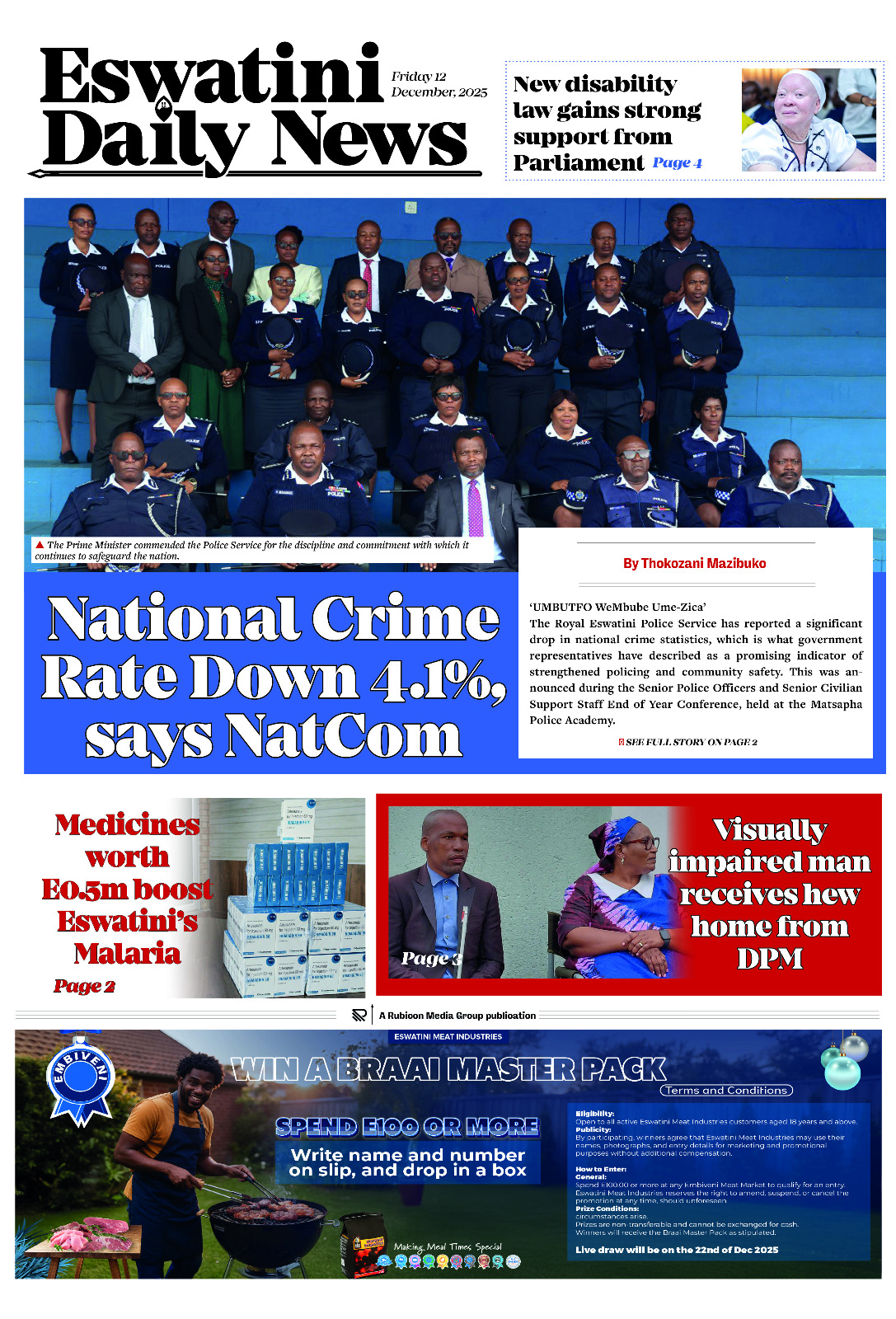

Eswatini’s cultural activities are recognised as contributing significantly to sustainability. Moses Vilakati, African Union Director of Agriculture, Rural Development, Blue Economy, and Sustainable Environment and former Minister of Tourism and Environmental Affairs, describes the Kingdom as Africa’s sustainability pulpit precisely because of its eco-friendly traditions.

Vilakati highlights ceremonies like Umhlanga and Lusekwane, which serve ecological functions. For instance, the annual harvesting of reeds (umhlanga) during Umhlanga reduces the spread of common reeds harmful to wetland habitats, promoting healthy ecosystems vital for water purification and wildlife.

Similarly, during the Incwala ceremony, cutting the invasive lusekwane (acacia) fosters the growth of native grasses and plants by reducing canopy shading, helping maintain ecological balance.

Eswatini’s integration of indigenous and traditional knowledge into its climate agenda represents a powerful fusion of heritage and science.

These age-old practices offer sustainable, culturally grounded solutions for resilience, conservation, and climate adaptation.

As Dr. Dlamini puts it, “Indigenous knowledge is a major resource for climate adaptation,” but success depends on addressing governance challenges, strengthening collaboration among policymakers, scientists, and communities, and ensuring that ITK survives to guide future generations.

In embracing tradition, Eswatini shows how ancient wisdom can illuminate the path through today’s climate challenges, rooting climate actions in culture, community, and respect for nature.