Eswatini and Lesotho Join Forces to Reimagine Quality in Higher Education

By Staff Reporter

In an era where technology is rewriting the rules of education and employers demand more than just degrees, Eswatini and Lesotho are coming together to ask a bold question: what does “quality” really mean in higher education today?

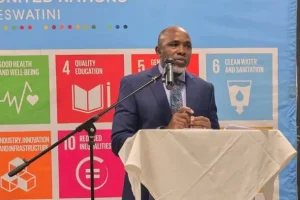

That question brought academics, education officials, and quality assurance experts from 21 institutions across the two countries to Mbabane last week for a UNESCO Capacity Building Workshop on Quality Assurance in Higher Education, a gathering that might quietly reshape how universities teach, assess, and prepare Africa’s next generation of thinkers and innovators.

The two-day workshop was hosted by the UNESCO Regional Office for Southern Africa (ROSA) in partnership with the Eswatini Higher Education Council (ESHEC) and Lesotho’s Council on Higher Education (CHE). It is part of UNESCO’s Campus Africa Flagship Programme, which is rolling out across the SADC region, following earlier sessions in Zimbabwe and Zambia.

While the setting was formal, the mood was alive with ideas, educators trading notes on everything from digital transformation and curriculum reform to cross-border recognition of qualifications.

At its heart, the message was simple but profound: quality in education must be reimagined, not inherited.

As Eswatini’s Nhlanhla Dlamini, Executive Secretary of the Teaching Service Commission, put it, the gathering was about more than technical checklists.

“This workshop represents a reaffirmation of our shared commitment to academic excellence, regional cooperation, and sustainable development,” he said. “It strengthens institutions, empowers professionals, and creates pathways for collective progress.”

In both Eswatini and Lesotho, higher education has grown rapidly over the past two decades. But rapid growth brings new pressures, keeping curricula relevant to evolving job markets, ensuring digital access for rural students, and maintaining academic integrity as AI tools become part of everyday learning.

That’s why, as participants agreed, “quality” can no longer just mean compliance with rules or ticking accreditation boxes. It must mean meaningful education, one that prepares students to think critically, innovate, and solve problems that matter.

One of the liveliest discussions at the workshop focused on digital transformation.

Universities across the region are embracing online learning, virtual libraries, and data-driven teaching tools. But the shift has also exposed deep inequalities between students with stable internet and those without, and between institutions that can afford modern systems and those struggling to stay afloat.

Participants shared experiences on how to make technology work for learning, not against it. This includes training lecturers in digital pedagogy, ensuring reliable infrastructure, and developing frameworks to evaluate quality in online courses.

Dr. Moeketsi Letele, Chief Executive of the Council on Higher Education of Lesotho, said technology should not be feared but harnessed.

“The workshop inspired Eswatini and Lesotho to take bold steps, including ratifying UNESCO’s Global Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications,” he said.

“Digital transformation is reshaping our universities, but with the right frameworks, it can also make our education systems more inclusive, resilient, and globally competitive.”

Another key focus was curriculum relevance. In a fast-changing economy, students need more than memorized theory, they need real-world skills.

Experts encouraged universities to embrace competency-based education, where teaching and assessment focus on applied knowledge, creativity, teamwork, and problem-solving. This approach, participants noted, makes graduates not just employable, but adaptable, a quality employers value most.

Institutions were urged to align national curricula with regional frameworks such as the Addis Convention and UNESCO’s Global Convention on Recognition of Qualifications, to ensure that Eswatini and Lesotho graduates can compete and move freely across the continent.

“Quality assurance should not be about static compliance,” one facilitator said, “it should drive renewal, keeping education alive and relevant to today’s realities.”

Perhaps the workshop’s most powerful lesson was that no institution can achieve quality alone.

Through peer learning and open dialogue, participants agreed that regional collaboration, sharing expertise, benchmarking performance, and learning from each other’s challenges, is the backbone of progress.

George Wachira, UN Resident Coordinator in Eswatini, summed it up: “Regions with strong and coherent education systems earn greater credibility, attract investment, and engage effectively in the global knowledge economy.

Quality education doesn’t just empower individuals, it uplifts nations.”

The conversations didn’t end with the workshop. New cross-border working groups and professional networks were established, promising ongoing cooperation between Eswatini and Lesotho on quality assurance standards, joint training, and policy exchange.

Dr. Peter J. Wells, Head of Education at UNESCO ROSA, called the workshop “a milestone” for the region.

“The solutions Eswatini and Lesotho need are in this room,” he said. “Quality assurance isn’t someone else’s job, it’s our joint endeavour. Every idea shared and every partnership formed here moves our region closer to a stronger, fairer, and more relevant education system.”

As UNESCO continues the initiative across SADC member states, the goal is to create an interconnected higher education space where quality standards, mutual recognition of qualifications, and academic mobility become the norm, not the exception.

The impact of such collaborations may seem distant to the average student today, but the outcomes are deeply practical:

Better teaching that blends digital tools with real-world application.

Stronger institutions with clear standards and reliable assessments.

More opportunities for graduates to study, work, or teach across the region.

Greater confidence in the value of local degrees on a global stage.

In essence, this is about restoring trust that a student’s hard work will translate into real opportunity.