Eswatini clears IMF debt

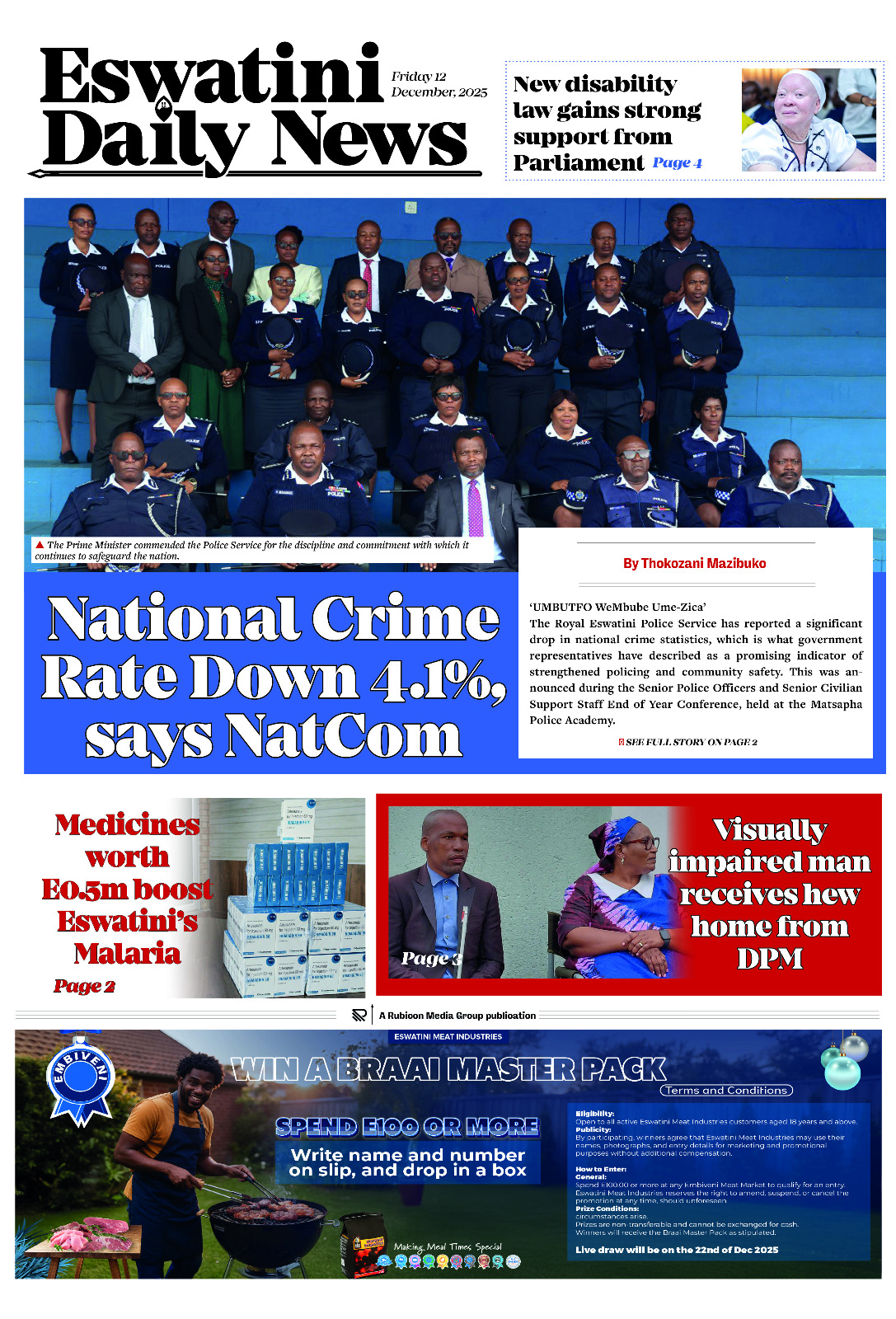

Minister of Finance Neal Rijkenberg

Minister of Finance Neal Rijkenberg

By Delisa Magagula

Eswatini has fully repaid its emergency loan to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), marking a significant milestone in the country’s financial management.

The repayment makes the kingdom one of the few countries in the region to have settled its IMF debt in full, even as the government turns to the World Bank, the African Development Bank (AfDB), and other lenders for new financing to manage arrears.

The IMF loan was taken in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic under the Fund’s Rapid Financing Instrument. The facility was designed to help countries mitigate the economic and health impacts of the pandemic by providing immediate liquidity.

In Eswatini’s case, however, repayment terms were strict and the period allowed for repayment unusually short.

Speaking in response to questions from the Eswatini Sunday, Minister of Finance Neal Rijkernberg explained why the government prioritised repaying the IMF loan while pursuing new borrowing elsewhere.

The minister said the IMF loan carried a two-year grace period followed by a three-year repayment window.

“It’s a very aggressive repayment period and puts huge pressure on government finances,” Rijkenberg said.

By contrast, loans from the World Bank and AfDB typically offer softer conditions. Repayment can stretch across 10 to 25 years, with grace periods of three to five years.

“That is a lot softer, a lot easier to repay than these ones with very aggressive repayment periods,” he said.

Rijkenberg added that the government intends to preserve the IMF facility as a reserve for potential emergencies.

“The beauty of an IMF loan is speed. In Covid, we applied and in three weeks, the money was in Eswatini. With the World Bank, it takes about a year before a loan is approved. So we plan to leave the IMF as a backup in case of emergencies,” he said.

According to him, keeping the IMF option open provides the government with quick access to liquidity in the event of future shocks.

“Other African countries are not doing that.

Let’s hope there’s no emergency, because under an emergency, it would be tougher for them to access money,” he said.

The repayment of the IMF loan comes against the backdrop of longstanding domestic arrears. Many local suppliers, including small businesses, have gone unpaid for months or years due to fiscal constraints.

The minister said the $100 million loan secured from the World Bank earlier this year was intended to stabilise cash flow and ensure suppliers were paid on time during the current financial year.

He added that two more loans have been submitted to Parliament: a $50 million facility from OPEC and a $47.5 million loan from the AfDB.

“Our commitment is that these two loans will settle arrears once and for all,” Rijkenberg said.

He said the government was hopeful that Parliament would pass the loans within the next month to six weeks.

“If that happens, we will be able to settle arrears in Eswatini, and we believe that will be the last of arrears. That is really our ambition,” he said.

The minister also emphasised that Eswatini has not been accumulating new arrears in recent years.

“Over the previous seven years, we have been slowly but surely reducing arrears, proving that the financial parameters are in place to ensure we don’t overspend the budget,” he said.

According to him, fiscal reforms and existing legal frameworks now prevent the government from incurring arrears beyond the approved budget.

“The laws are there that prevent us from overspending, and history now shows we have stopped the accumulation of arrears,” he said.

The World Bank’s approval of the $100 million facility required Eswatini to meet nine prior actions. While Rijkenberg did not recall all of them offhand, he confirmed that reforms were part of the package.

World Bank documentation indicates that such prior actions typically include measures to strengthen public financial management, increase transparency in debt reporting, and improve fiscal discipline.

These conditions are designed to ensure that countries avoid slipping back into arrears and maintain a sustainable debt path.

The minister said the government’s track record of reducing arrears over the past seven years demonstrates progress. He also noted that with the new loans, Eswatini’s cash.

Worth noting is that Eswatini’s repayment of its IMF loan stands out in a region where many countries continue to carry substantial IMF obligations.

In Southern Africa, Zambia defaulted on its Eurobond payments in 2020 and continues to work with the IMF on debt restructuring.

Malawi and Mozambique have ongoing IMF programmes, while South Africa has avoided direct IMF borrowing but faces a growing public debt-to-GDP ratio.

By clearing its IMF debt, Eswatini gains room to manoeuvre in case of emergencies, even as it turns to longer-term financing for structural needs.

Analysts note that IMF loans are generally the fastest to access but come with the most demanding repayment schedules, while World Bank and AfDB loans are slower to process but more manageable over time.

In South Africa, for example, IMF loans have been used sparingly because of the political and economic implications.

Eswatini’s case highlights a pragmatic choice: using IMF funding in a crisis, but moving swiftly to clear it once conditions stabilise.

For local businesses, the repayment of IMF debt is less visible than the settlement of arrears. Many companies supplying goods and services to the government have been forced to operate with limited cash flow due to delayed payments.

Rijkenberg said the new loans before Parliament would ensure that suppliers are paid. “We believe arrears will be a thing of the past once these loans are approved and paid out,” he said.

The minister reiterated that the government has avoided overspending in recent years, which should prevent arrears from recurring.

“History has now also shown over the last period that we have stopped the accumulation of arrears,” he said.

Eswatini’s decision to repay the IMF loan while shifting to World Bank and AfDB financing reflects a broader strategy of balancing immediate fiscal pressure with long-term stability.

Rijkenberg said that maintaining access to IMF facilities for emergencies, while using softer loans for structural needs, provides the government with flexibility.

“We plan to leave the IMF as a backup in case of emergencies,” he said.

At the same time, he stressed that the government remains committed to fiscal discipline.

“The laws are there that prevent us from overspending, and history now shows we have stopped the accumulation of arrears,” he said.

The Minister further said, as Eswatini turns the page on its IMF debt, attention will shift to how effectively the government uses new financing to clear arrears and restore confidence among local businesses.

The outcome will test whether fiscal reforms and external loans can combine to put the country’s finances on a sustainable path.